How to save a language when its people disappear

Part 2 of Brian and Dawn Hadfield’s epic desert life

This is the second part of the story of Brian and Dawn Hadfield, who spent 60 years in outback Western Australia among the local Aboriginal peoples. (Click here to read Part One and find out more about their life at Cundeelee Mission Station.)

When Sydney girl Dawn Hadfield arrived in the middle of the Western Australian desert, 22 years young and all alone, she couldn’t speak a word of the local Aboriginal language.

But after beginning her missionary service at Cundeelee Mission Station in 1958, this was a deficit she quickly started to address.

In order to start documenting the language, Dawn was invited by the mission station’s superintendent to attend a short course at the Summer Institute of Linguistics (established by Wycliffe Bible Translators Australia) in Melbourne. On return from this training, Dawn spent time with the Aboriginal women living at Cundeelee – who were drawn together from interrelated people groups, so they spoke about five sub-dialects of the Pitjantjatjara language of the Western Desert people.

Dawn always had a pencil and a notepad with her, especially when she joined the women on hunting trips out in the bush. Over time, she recorded many words in the mish-mash of local dialects that became unique to the Aboriginal peoples at Cundeelee. This language became known as Cundeelee Wangka.

“She produced five different preliminary papers on the language, from the sound system to the phonetics and grammar,” says now 86-year-old Brian, Dawn’s husband.

“The papers were never published because when she shared this work with Bill Douglas [known as Wilf Douglas, a well-known missionary and the first person to document the writing and teaching of the Western Desert Language, in 1957], it verified what he suspected, that it was part of the Western Desert Language [WDL] group. It was a different dialect, but not a different language.”

Brian explains that the WDL group “stretches across the boundary of South Australia and up into the bottom edge of the Northern Territory”.

He sounds out some of the nuanced differences between particular words in the different dialects that fall under the WDL umbrella. To the untrained ear, they are difficult to identify. Brian himself admits that when he arrived at Cundeelee station, along with Dawn’s lessons, he needed supernatural help to learn Cundeelee Wangka.

“I wasn’t getting anywhere with the language – I just couldn’t take anything in. After two weeks I prayed, ‘Lord, please help me to understand it,’ and then it just happened. I could close my eyes, I could see a word and repeat it. I thought, ‘Wow! Thank you Lord.'”

As Brian gained fluency in the language he began to teach men, while Dawn taught the women.

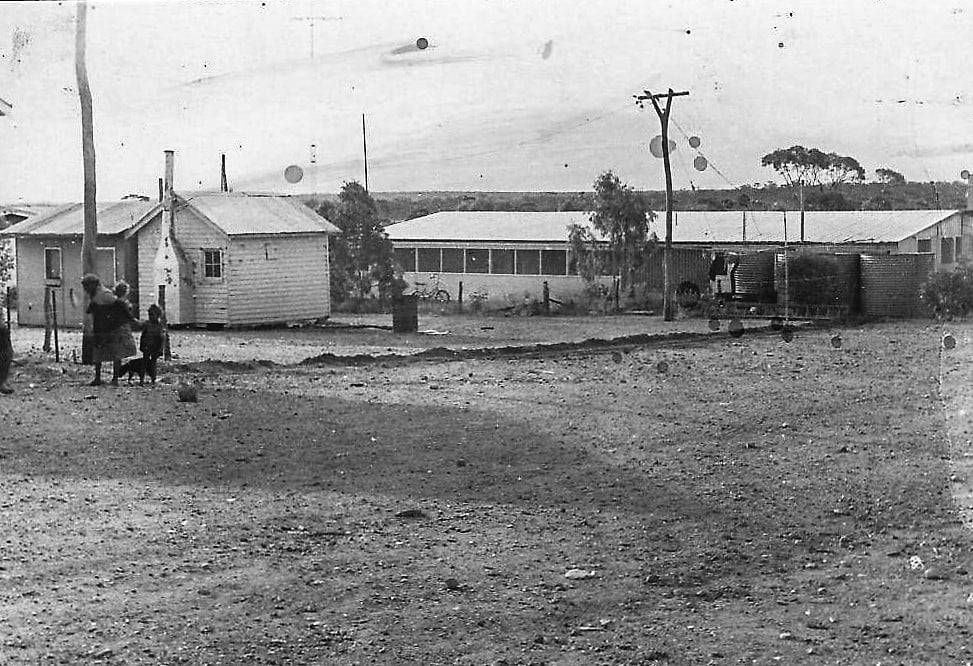

Cundeelee’s six-bed hospital with outpatients’ accommodation.

During the 1970s, Dawn and Brian created resources to teach Cundeelee Wangka in the school on the mission station.

“At Cundeelee we tried our best,” says Brian. “We set up three times to go into the school. We had it all prepared – all our own work, with no involvement from the education department. We structured the curriculum for teaching kids in school their own language, and three times it was negated. The Western Australian Education Department was just not interested.

“Fortunately, Aboriginal languages are now being taught in schools. So things have changed in the last five years.”

Undaunted, the Hadfields continued their work in preserving the local language, even after leaving the mission station in 1980 and moving to Kalgoorlie so their children could complete high school.

Just one year earlier, their Cundeelee Wangka Learning Course and grammar was taped and printed at Mt Lawley College of Advanced Education.

The pair continued to gain more training in translation as Dawn kept working on a Cundeelee Wangka dictionary (soon to be published in conjunction with the Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre).

Meanwhile, in the mid-1980s, Cundeelee Mission Station was closed due to a lack of access to water. The Aboriginal community was moved to a purpose-built village, ten kilometres south of the Trans-Australian railway station of Coonana.

“I would start teaching them, from the Bible, their language.” – Brian Hadfield

Brian and Dawn kept up regular visits to the communities of Coonana and Tjuntjuntjara, where they helped local Aboriginal people to learn to read in their own language. They also read the Pitjantjatjara Scriptures to them, making use of the teaching material they had produced.

“We had a lot of teaching material and any opportunity I got with an Aboriginal person in this village in the desert, I would read the Scriptures to [them],” says Brian.

The community at Coonana slowly dissolved over the years, as people moved away, with most returning to their former homeland at Tjuntjuntjara (700 kilometres north-east of Kalgoorlie).

“It’s only been the last three years really that I haven’t been able to visit them. It’s been a lifelong connection,” says Brian.

Brian and Dawn Hadfield being filmed this year reading the Bible in Pitjantjatjara. Kalgoorlie Baptist Church

And while his trips into the desert may have come to an end, his connection with Cundeelee’s Aboriginal community certainly hasn’t.

Nine years ago, Brian first began making visits to the local prison at Kalgoorlie-Boulder (Eastern Goldfields Regional Prison).

“It all started through language,” he reflects.

“I met a younger man, Tjamu, who was the eldest son of my favourite Cundeelee Wangka language ‘tutor’. I asked him, ‘Would you like to hear the story your dad recorded over there in Brisbane [at a Summer Institute of Linguistics workshop in 1964], which he sent to his ngultju – his family and friends – back home at Cundeelee?”

“Tjamu said, ‘Yeah I would love that.’

“So I applied to the jail to have a visit with him. I sat down with Tjamu, and as I read from the paper on which his dad’s words were recorded, half a dozen or more young fellas gathered around to listen, some of them from the Warburton Ranges, nearly 1000 kilometres north-east of Kalgoorlie. They were hearing a foreigner speak Pitjantjatjara. They really enjoyed it and warmed to it.”

“If they were open to it, I would read the Pitjantjatjara Scriptures and they would sit really glued to it.” – Brian Hadfield

So Brian became part of the prison’s chaplaincy team and began making regular visits.

He continues, “I just sat down and started talking with people and got to know where they were at. If they were open to it, I would read the Pitjantjatjara Scriptures and they would sit really glued to it.”

“These years in prison ministry have been great, always with eager listeners, and others showing interest in reading in their language.”

This year, after COVID restrictions eased, Brian began teaching the Pitjantjatjara language to several men in the jail, after a request by one Cundeelee man, also named Tjamu (whose parents and grandparents Brian had known well).

“This was arranged with the authorities. Four men participated, but three dropped off for various reasons. One, who is now back from Perth, is keen to get going again, because he wants to learn his grandfather’s language,” says Brian.

Brian and Tjamu (number two) were invited to open the prison’s NAIDOC week ceremony last November.

“I took this opportunity to introduce Tjamu into the art of translating the Lord’s Prayer into his own dialect. So Tjamu very confidently opened the ceremony with reading the Lord’s Prayer in ‘Tjaa Uti Kantililitja’ — the ‘Understood/Clear Language of the Cundeelee People’, and I read the English. It was very well received,” says Brian.

The pair recently did the same for the jail’s Christmas celebration, by translating the Bible passage Luke 2:8-16, where the the angel tells the shepherds about the birth of Jesus.

“Tjamu went beyond reading Pitjantjatjara, into reading and writing, then to translating his own ‘Tjaa Uti’, from English. So now Tjamu not only reads Pitjantjatjara, but also reads and will be more involved in writing and translating in his own language,” says Brian.

He adds, modestly, “That is satisfying. Our desire and purpose always has been to see a literate people who could read the Bible in their own language.”

With thanks to Kalgoorlie Baptist Church for helping supply photos based on their video about the Hadfields.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?