Outlawed 1631 'Adulterous Bible' discovered in New Zealand

This typo is of biblical proportions

In these days of fast-typed emails and text messages, typos can seem so common that they almost don’t matter. There’s often an edit button on social media that can quickly rectify the situation – or at least the opportunity to reply with a * and correction.

Unfortunately, corrections were not so easily managed in 1631 when printers Robert Barker and Martin Lucas printed 1000 copies of the Bible with a typo of biblical proportions. “Thou shalt commit adultery”, read Exodus 20:14 – with the small but essential word “not” missing.

When the mistake was discovered one year later – a concerning detail which indicates one thousand Bible owners had not gotten around to reading the ten commandments – Barker and Lucas were summoned to the court of King Charles I.

Charles admonished them for their incompetent workmanship and the scandalous result, stripping them of their printing license and declaring a fine of 300 pounds. All but twenty of the texts were destroyed.

With only twenty copies escaping royal wrath, the controversial text – referred to as The Wicked Bible, The Sinners’ Bible and The Adulterous Bible – is a rare find today. And even more so in the Southern Hemisphere, where until now, no copies have been reported as found.

But all that changed yesterday when Chris Jones, an associate professor in medieval studies at the university and fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in London, announced that a copy had been found in Christchurch, New Zealand.

A former student of Jones’s brought the copy to him in 2018. Her family had acquired it two years earlier at a deceased estate sale of the late owner, bookbinder Don Hampshire. Hampshire came to New Zealand from the UK in the late 1950s and died in Christchurch in 2009. No record has been found of him having revealed his ownership of the scandalous book.

“They are not things that you just walk into an office having found one in a garage in Christchurch.”

Jones’s former student told him she believed it was a “Wicked” Bible, but he was “very disbelieving because these are not common items”.

“They are not things that you just walk into an office having found one in a garage in Christchurch. But I looked at it and I thought, wow, this is exactly what my former student thinks it is – it’s a Wicked Bible. I was blown away by it,” Jones told The Guardian NZ.

The delay in announcing the discovery to the world was not, as it turns out, the glacial pace of life in New Zealand. Instead, the University of Canterbury in Christchurch chose to keep the discovery a secret to allow researchers and book conservers enough time to study and preserve the book.

“It’s a mystery, it’s fascinating and it has made its way halfway around the world,” Chris Jones, an associate professor in medieval studies at the university and fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in London, said on Monday.

Jones studied up on the Bible’s history, stories explaining how the mistake was made, and the printing industry of the time. He said while there are wild theories that it could have been a deliberate act of industrial sabotage by a rival printer, it is far more likely the printers, who were operating in a cut-throat industry, were cutting costs on copy-editors. As such, it stands as an excellent reminder to those overseeing media organisations today.

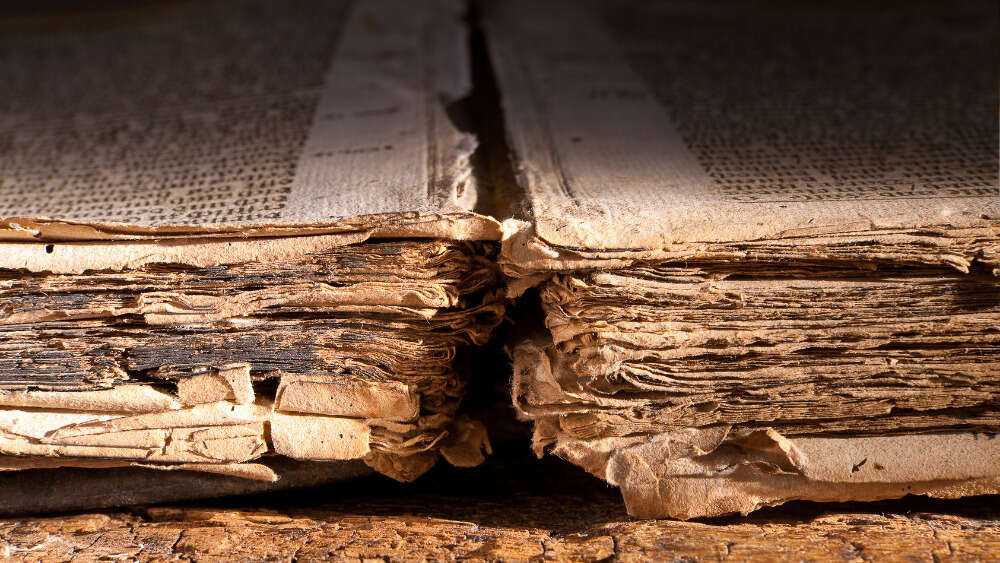

The Bible is now owned by the Phil and Louise Donnithorne Family Trust. Unlike many Bibles, the Bible does not contain family trees, rendering its former life a mystery. It contains just one illegible name and was in relatively poor condition when it was re-discovered, with its cover missing, some water damage, and a few pages at the back gone for good.

However, the copy does contain some unique features and is one of only a few copies that have the more decorative red and black ink.

The Bible has now been fitted with a new cover by Book and Paper Conservator Sarah Askey, who has conserved and preserved it for future generations. She also documented any clues about the book’s history, such as plant remnants, human hair and textile fibres preserved between the pages.

Despite the illegible handwriting, Jones is hoping someone might be able to shed some light on the Bible’s former owner when a digital copy of it becomes available to the public soon.

“I’m hoping someone will come and say ‘Chris Jones, you’re an idiot, this is really obvious’, and I look forward to it.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?