Living in Love and Faith: A light at the end of the tunnel?

A gay Christian looks at the Church of Englands new LGBT resource

As an Australian studying at Oxford who is gay, celibate and Christian, David Bennett has a unique perspective on the Church of England’s struggles over human sexuality. Bennett took part in the Church of England’s video response to the Living in Love and Faith report – the Church’s invitation to a debate.

As a gay Christian, you often can be confronted with two possible trajectories for pursuing your faith. One way looks something like joining the Episcopalian Church in the US, which is in decline and has little space for the Scriptures. The other way seems to be part of an evangelical world that won’t even allow you to identify with others who have the same experience of being differently embodied.

The Church of England is an important space that has refused either way. This is important in a world where you either embrace revisionist teaching – which just doesn’t add up theologically – or you embrace the view which denies any of the reality related to LGBTQI+ identity, which is harmful for the self.

I’ve always been one to disagree and to seek a deeper third way which emphasises the real encounter with the love of God in Christ that leads to deeper discipleship.

When I first heard of the Living in Love and Faith (LLF) process now happening in the Church of England, I was honestly filled with hope. To know that the Church would listen to people from across the spectrum of beliefs and experiences was a sorely lacking element in the polarised landscape of discussing sexuality and faith.

Last month, the Church of England released LLF’s long-awaited suite of resources which remains unrivalled in the Christian Church, in terms of its depth of treatment, as well as its diversity of enquiry and consultation with LGBTQI/SSA people in its midst.

But as a celibate gay Christian, instead of being excited, I had a deep reluctance to having something questioned so intensely that canvasses your whole person and then, again, brought to the fore.

I felt as if I was already exhausted by constant enquiries, or by the treating of the marriage question as something that is “up in the air”. I knew that what would resurface is the pain, wounds and persecution suffered by people invested in that tough question. I also knew I would have to re-articulate my own view and risk suffering again.

I have dear friends who disagree with me and re-articulating my position also would hurt them, and vice-versa.

In light of the LLF‘s formation and circulation, I just desired to know that a belief in God’s image in marriage would be upheld, and also my vocation in that.

As the Church of England website states, “The Living in Love and Faith book sets out to inspire people to think more deeply about what it means to be human and to live in love and faith with one another. It tackles the tough questions and the divisions among Christians about what it means to be holy in a society in which understandings and practices of gender, sexuality and marriage continue to change.”

I honestly wanted to receive that inspiration but what I really desired was the love of a church leader to say, “well done, keep going.”

My prayer is that we could as a Church find a route of convergence but not at the expense of truth.

What the LLF process highlights is that we can’t go forward without listening more closely to those with whom we disagree. However, the cost to actual LGBTQI+ people in the church of listening to each other is not catered for in a way that could make the conversation “safe”. As Christians we are called to a form of listening that is deeply costly to one’s own convictions, as you hear someone articulate a view which runs against the whole trajectory of your internal life.

In his recent essay on Living and Love and Faith, Oliver O’Donovan, one of Anglicanism’s foremost theologians, states: “What initially promises to be a rather dispersed and ill-focused address to the question turns out, happily, to be the opposite. There is intellectual integrity to these reflections. If the paradox is permissible, they are ‘classically post-modern.’ Reflection begins from the church’s doctrine as found, unchallenged until recent days: marriage is a lifelong union between one man and one woman. This is not presented as a problem to be got round, but as a deep-rooted existing commitment bound up with Christian faith in the place of both men and women in God’s creation.”

The only problem with a postmodern treatment of the marriage question, which the world has already gone through, is that it leaves you to pick up the pieces – to reconstruct. Next to the pain, that is a load too hard to bear for all of us, even more so for a largely ignored minority like celibate gay Christians. As O’Donovan states, however, “only multiple authorship can discover a route to convergence”.

My prayer is that we could as a Church find that route of convergence but not at the expense of truth.

Convergence can’t be found unless voices are also able to respond to the materials with a re-articulation. The Church of England Evangelical Council’s half-hour video called The Beautiful Story (TBS) was organised to achieve this purpose, which I was involved in filming. It consisted of a consensus across a highly diverse array of evangelical Anglican voices in the UK, including many involved in the LLF process. The video re-affirmed our belief in marriage and sexuality as set out in the Church’s liturgy and teaching.

As soon as the video was released, a flurry of revisionist voices on Twitter responded – many of them LGBTIQI+ clergy or lay people, with their partners. In most cases, they decried The Beautiful Story‘s message.

As Andrew Goddard – an evangelical member of the LLF process, Christian ethicist and board member of CEEC – stated in response to the attacks against it: ‘It seems to me that part of what LLF is doing in the Church of England is helping us all face the truth about where we are as a church rather than hiding away in our different parts of the church and pretending others aren’t there, or even wishing that they would go away and not be there. Facing the truth is not going to be easy. It’s going to be hard and painful. But it is probably what we all need to find the courage and honesty to do.”

The LLF conversations can throw us back on Jesus and who he is.

It seemed in this moment of backlash against The Beautiful Story that we were back to square one where it became incredibly difficult – even with the investment of LLF – for the Church of England to find a “light” at the end of the tunnel.

After all, we are called as Christians to articulate hard truths which hurt and love in the midst of them. They hurt ourselves when we need to face our own failures and sins, and they also hurt others, who need loving challenge – but never for the sake of harm.

As I see it, the LLF conversations can throw us back on Jesus and who he is.

What we need is for Jesus to be leading this as the Lord of the Church of England and a movement of prayer at the helm.

Unless that is front and centre, our human fallibilities will compromise the process and it risks falling prey to a political agenda that won’t produce the fruit of righteousness. This conversation, if we can prayerfully continue, could have the potential to bring us back Jesus, who is after all the way, the truth and life, the light at the end of this dark tunnel.

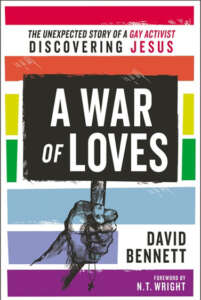

David Bennett is completing his D. Phil at Oxford University. He is the author of A War of Loves published by Zondervan, which describes his unexpected journey from gay activism and a distrust of religion, to becoming a follower of Jesus.

David Bennett is completing his D. Phil at Oxford University. He is the author of A War of Loves published by Zondervan, which describes his unexpected journey from gay activism and a distrust of religion, to becoming a follower of Jesus.