On this World Teacher’s Day, I pay my respects to all teachers and offer this account of one of the most influential teacher-student-teacher relationships in history, Ælberht and Alcuin of York.

In the mid-700s, the cathedral school of York was arguably Europe’s greatest centre of learning. The head of the school was the gifted Ælberht, later the Archbishop of York. He insisted that his students learn more than just how to read the Bible and calculate the dates of the church calendar (the focus of many earlier schools). He wanted them to learn for learning’s sake, and only then to apply what they knew to understand the things of God.

Sometime in the 740s, a boy entered the school who would go on to change Europe. His name was Alcuin. As the son of semi-noble parents, Alcuin was expected to get the best education available and then to contribute to society.

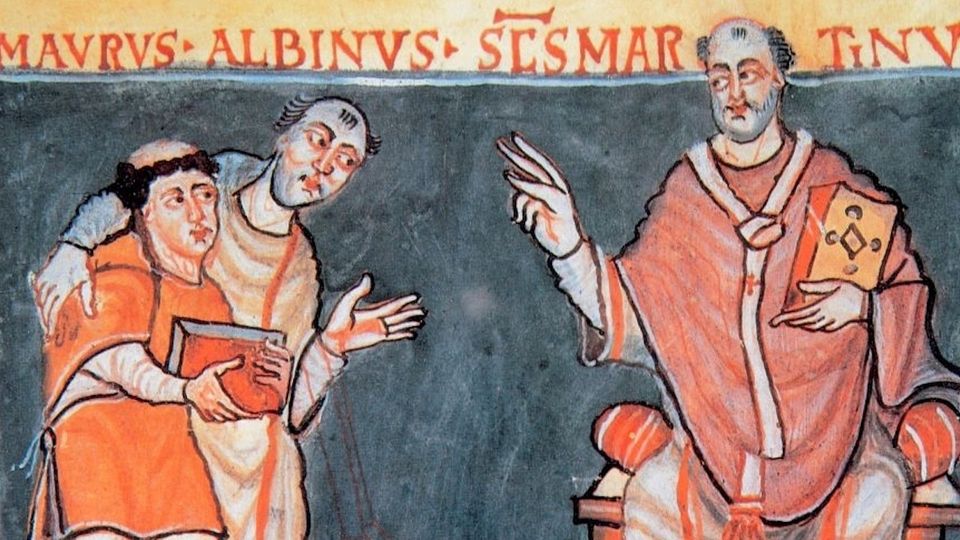

Alcuin excelled in his studies beyond all others, and he developed an intense love for the Christian faith. Both things would animate his long career. Alcuin became a teacher in the school and was chosen to accompany Ælberht on trips to the Continent, even to faraway Italy, collecting new books or new manuscripts of old books, Christian and classical (that is, pagan). Eventually, when his mentor Ælberht became archbishop in 766, Alcuin became head of the York school, around the age of 30. He was also ordained as a church deacon soon afterwards, a sign that he intended to direct his prodigious intellectual talent in the service of Christ.

Learning about God’s world is in itself an act of worship because it is searching out the signs of God’s own wisdom imprinted on creation.

Alcuin (like his teacher Ælberht) adopted an educational philosophy known as “wisdom-theology.” It is not as creepy as it sounds. It is an idea that goes back to biblical times. Wisdom-theology says that God made the universe through his genius, or wisdom. As a result, the world functions not in a haphazard manner but in accordance with deep rational principles, which, by God’s grace, our trained human wisdom can discover (at least in part). This educational perspective means that learning about God’s world is in itself an act of worship because it is searching out the signs of God’s own wisdom imprinted on creation.

Alcuin soon came to the attention of Charlemagne, the ruler of much of Europe. Charlemagne urged Alcuin to come to his court and act as both a personal adviser and a kind of Minister of Education. Alcuin agreed. And soon he was directing an extensive educational program in the monasteries and cathedrals of Europe, open to the rich and the poor, boys and (sometimes) girls.

Alcuin insisted on the seven “liberal arts.” The first three subjects made up the trivium or threefold-way: Grammar (Latin), formal Logic, and Rhetoric, or the study of the rules of persuasion. After completing the trivium, students entered the quadrivium or fourfold-way: Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy. Alcuin also demanded the highest quality handwriting from his students and fellow scholars, and his “Carolingian” script became the basis of modern non-cursive handwriting in the West. It is also the basis for Times New Roman font.

Studying grammar, logic, rhetoric, mathematics, music, astronomy, and all the rest was considered an act of devotion to the all-wise God.

The seven liberal arts promoted by Alcuin were very much the precursor to the serious scholarship that Ælberht and Alcuin, and many others, expected of themselves and all who would become teachers. Once the liberal arts had been mastered, students could move on to the serious subjects: history, natural history (physical sciences), and, of course, theology. A handbook for clergy from the 8th century makes clear that young priests were expected to have mastered the seven liberal arts, as well as some philosophy, before embarking on their theological and pastoral education. Other advanced subjects included medicine and the law.

Studying grammar, logic, rhetoric, mathematics, music, astronomy, and all the rest was considered an act of devotion to the all-wise God. It was learning about the “wisdom” the Creator had imprinted upon the world. For Alcuin and his circle, and all those they inspired, this involved knowing not just the Bible and the church fathers, such as Augustine, Gregory the Great, Jerome, and Ambrose, but also all of the ancient Greek and Roman (classical) authors they could get their hands on.

The story of a “dark ages” when the church suppressed knowledge is a fiction developed in modern times.

From Alcuin’s own catalogues, letters, and the surviving manuscripts from this period, we know these included Plato, Aristotle, Galen, Pliny the Elder, Horace, Cicero, Seneca, Virgil, Livy, Ovid, and about 60 other authors. The breadth of learning is remarkable.

The story of a “dark ages” when the church suppressed knowledge is a fiction developed in modern times. The tale is rarely contradicted today because so few of us learn about medieval Europe. Why would we bother? It was “the Dark Ages”!

But teachers have been producing students, some of whom would become teachers … in a long chain of transmission of (divine) wisdom that continues today.

God bless all the teachers of God’s wisdom—whether Science, English, Mathematics, Music, History, or Theology!

Dr John Dickson is a historian and author, and presenter of the Undeceptions podcast. This article is adapted from his latest book, Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?