Bridging the cultural gap to empower Indigenous leaders

Nungalinya College is wonderfully unique. Where else do you find a training college that brings Catholic, Anglican, Uniting Church and Lutheran, Baptist (and other!) Indigenous church leaders from across the Northern Territory to its campus in Darwin, to sit in class and be equipped for ministry together?

And it works, despite the tensions and misunderstandings that arise from the differing world views of Western culture and Aboriginal culture, of different understandings of time, space, land and language.

Nungalinya is a college that’s focused on equipping and empowering indigenous Christian leaders to do the work of theology and ministry. The college respects language and culture and land, and first nations people’s wisdom and relationships. Students attend for up to four weeks at a time, participating in Certificate and Diploma level courses.

Its success is partly a tribute to the unique role of its four Deans – one Catholic, one Uniting Church, one Lutheran/Baptist and one Anglican/other denominations – who play a key pastoral role more than an academic one.

It’s their job to communicate with communities and church leaders, match up the right people for the right courses and organise to fly or bus them in from far-flung communities to the Darwin campus for their block of studies.

Tony Goodluckand Bapa Ken Garrawurra, who trained at Nungalinya 40 years ago with Tony’s father, Jack Goodluck.

Once the students arrive in Nungalinya, the Deans give whatever pastoral support the students need to ensure they can attend chapel at 8.30 in the morning and be in their classes from 9am to 2.30pm each day.

“With the Deans you need someone who is a compassionate person with a pastor’s heart,” says Tony Goodluck, who until last year was the Dean for the Uniting Church and NRCC [Northern Regional Council of Congress] students.

“At the same time, we need someone who’s got an eye for detail, understands systems and numbers. It’s a rare and wonderful space to work in. And for me, the friendships and working in a team with the other deans was wonderful … it’s an absolute privilege to be in that space.”

Tony, who is now the Moderator of the Northern Synod of the Uniting Church, was a Nungalinya Dean for almost five years. As he relates some of the joys and challenges of the role, it becomes clear that it requires endless patience and persistence to overcome obstacles.

“You could hardly find two more different cultures in the world. And here we are working together in a college, which is a combined churches’ college.”

Eddie and Lottie Robertson in class during the Faith and Wellbeing course at Nungalinya College, Darwin

It’s the Deans’ job to bridge the cultural gap between the college and the communities. All its courses are VET sector courses, which involve formulas of attendance hours and assessments to demonstrate competencies.

Many students come first for a Foundation Studies course, which helps them improve their reading, writing, and numeracy in English (and biblical “literacy”) so that they are able to undertake other courses at a higher level. With more than 70 Aboriginal languages spoken in the NT, English is the only language in common, but there’s very low literacy and numeracy, particularly among younger generations.

“Most of our students would have three or four Aboriginal Languages and English would be their fourth or fifth language. So the first big thing is that Nungalinya is teaching in the third, fourth or fifth language of the majority of the students,” Tony comments.

“It’s fair to say the mainstream education system has largely failed the last two generations of Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory in terms of reading, writing, and numeracy. Those who studied at the Mission schools, who are around 60 now, have got quite strong reading, writing, and numeracy. So, somewhere over the last couple of generations, we’ve let things slip.”

Students can’t just come to Nungalinya, they have to be sponsored by their church. But even when they’re motivated to learn, the logistics of getting them from their communities to the college campus, considering the complexities of community life, is no mean feat.

“Let’s say we want to get 30 people in, that’s the ideal number for a Foundations Course. That means between the four deans we’re probably going to speak to somewhere between 75 to 80 different students who have applied and ask them if they are available to come in for a particular course.

“Of those, we might find, say, around 47 who say, ‘Yes, I can come, book me in,’ and we book travel for them about 10 days out from a course.

“So when you ring people back and say, ‘we booked you, this is the time’ they might reply, ‘oh no, sorry, my child’s unwell, or my sister fell over and hurt herself, I have to stay here. A body’s come back, we’ve got to be involved in that. Some ceremony’s come up.’ Whatever. And so we’re down to 36 or 37 and out of that, somewhere between 28 and 32 actually arrive.”

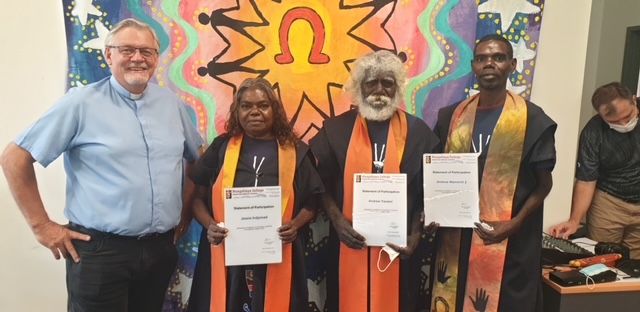

Tony Goodluck with Jessie Indjamad, Andrew Yarmirr and Andrew Wanimilil 2 on graduation night for the Art and Faith course at Nungalinya College

On Tony’s first weekend five years ago, when he was bringing people in, he received 28 phone calls, texts and emails, which he thought was a lot, but within three months, he learned that it wasn’t.

“Typically, I would have between 55 and 60 communications on a weekend. The busiest weekend I ever had with communications over the five years was a three-day weekend where I had 120 texts, phone calls, emails, et cetera.”

To illustrate the complications involved, he tells the story of a Yolŋu woman who rang him from her house one morning wanting to know where her plane was. It was already waiting for her at the airport but she was waiting to see it land. When she didn’t arrive, the plane took off without her.

So Tony rang MAF (Mission Aviation Fellowship), who got in touch with the pilot, who turned around and came back for her.

“I’m ringing the woman back saying, ‘I know Yolŋu don’t like to run unless you’re hunting. I want you to hunt for that plane, run to the airport with your bag, because now we’re running out of time.’”

Unfortunately, when she arrived at another community to catch her connecting flight, the gates were closed and she wasn’t able to get on the second plane. So now she was stuck in the wrong community.

“So I said to the MAF people, ‘What are we going to do?’ And they said, ‘Well, we can take her to a third community. And then that plane is flying back to her community, but we can’t guarantee there’ll be a seat.’ I said, ‘So she could be stuck in this community or that community, but you can’t get her home.’ They said ‘That’s right.’ In the end, they did an extra flight and flew her home and we booked her on a plane two days later. And she came into the course a day late, only to find out on the second day of the course that others hadn’t been able to make it either, and so the course was cancelled. So we sent her home on the Wednesday. She came back four months later and did the course.”

“It’s certainly not a science. And that’s why I say 76 calls for 47 bookings, with 36 who say they’re coming for 28 to 32 to arrive. It’s remarkable how often those numbers work out – probably 80 to 90 per cent of the time. We never know with any particular student whether they’re actually going to get there or not.”

“There were times when it took, let’s say 15 phone calls over two weeks to get in touch with someone because people change their number often, maybe three or four times a year. So I might have the number from six months ago, but they’ve changed phone numbers.

“So it’s not enough just to know what their phone number is, but I have to have an idea of who their relatives are or if they work, where they work. If there’s a landline, that’s pure gold – because they stay the same. Or we call the church leader and say, ‘are you able to get a message to so-and-so?’ And the answer typically is ‘Yes, I’ll tell them if I see them ….’

“Often we put feelers out in four or five, maybe six different directions – one through the clinic, one through the shop, one through the Shire office, one through a church leader, one to someone’s sister, and quite often, you get a call back and someone would say, ‘Yo, I’m sitting under this tree here – you know, that big shade tree down there near the shop,’ ‘Yo, I know that one.’ ‘And the sister of that one you want to speak to just came walking past. So I told her to get her sister to call me, but now I’m going to her house and we’ll ring you from there.’

“So the Deans are taking up the different timeframes, the different understandings of time, the different understandings of priorities and values to bring people into the class so that the teachers can teach. And there’s a lot of tension in that space between the two cultures, but the Dean’s role is to deal with as much of that tension so that the teachers and the admin staff are dealing with as little of that as they need to.”

The other half of the Dean’s role is supporting the students once they are living on the campus.

“It can just go crazy when students are in because they need support with things,” says Tony.

That pastoral support often begins with a small need such as finding some Panadol or a Band-Aid or asking the Student Support Officer to arrange a doctor’s appointment.

“Sometimes our students might be struggling to wake up early in the morning. Their lifestyle at home might be that they worship at fellowship until 11.30 or midnight, and then go home and sit around and talk until 2 or 3am, sleep through to midday and then get up again. When they come in and we want them in chapel at 8.30 in the morning, that’s a huge shock.”

Chapel served to alert Tony to who was absent, so he would go and check on them in their room.

“My point of view, as a Dean, was always that I need to go and check if that person is okay, it’s up to them to get to class – they’re adults. They’re not children. They’re mature adults and it’s up to them to get to class. If they’re not there, why aren’t they there? Maybe they’re feeling sick. Maybe they just slept in.

“Maybe they’ve got the curtains pulled and someone’s been on the phone to them late at night, and they’ve only just got to sleep; and so I go and knock on the door. Stand back, wait a minute. Knock on the door. Call out, stand back, wait a minute. Knock on the door. Call out. Quite often, it’s on the third time, ‘Oh, this bloke, he won’t go away unless I answer the door.’

“So first thing is to check whether someone’s okay, and quite often it was just ‘Oh, I’ve slept in’ … and people get up and get to class a few minutes late, or they might be sick, in which case we then ascertain whether they just need to sleep a bit or whether we need to get the Student Support Officer up to talk to them, particularly if it’s some women’s business, and see whether they need to see a doctor or not.”

Tony says the levels of chronic illness among First Nations students are “unbelievable. Most people aged 35 or older are dealing with multiple chronic illnesses. It’s completely unacceptable.” He gets choked up as he relates the problems – diabetes, chronic heart disease, knees that are so painful people have difficulty walking, renal failure, asthma, MJD (Machado-Joseph Disease, a degenerative neurological disease).

I say: “This obviously upsets you.” He responds: “We were so hopeful 40 years ago that we were on the right track.”

Tony says that in the five years he had at Nungalinya, with 35 or 36 weeks of student contact a year, “there wasn’t one week went by when there wasn’t a death of a close family member of one of the students who was currently in at Nungalinya.

“And I mean, close family member – your brother, sister, cousin, mother, father, aunty, child, close family, at least one death every week. So people are dealing with unresolved grief on unresolved grief on unresolved grief. And they still want to come and delve into the Scriptures and hear the words of Jesus and develop skills so they can take them back to their community and their families.”

You often don’t see the fruit of this kind of work, Tony says, but he was blessed to see it at Easter when he visited Milingimbi Island.

You often don’t see the fruit of this kind of work, Tony says, but he was blessed to see it at Easter when he visited Milingimbi Island.

“Every night, there was fellowship with over 200 people that would go on to 11.30 or midnight. They did re-enactments of the last supper and Good Friday, Jesus carrying a cross around town and people yelling and calling him names and the dogs barking and all of that. Crucifixion, tomb, and on Saturday night, probably over a hundred people slept in the park, close to the closed tomb, near the new crosses that have been put in the ground on the Easter Thursday and waiting in anticipation for early on the first morning of the week,” he relates.

“We can think we’re pretty committed in getting up for a Dawn Service on Easter Day. That’s nothing. At Milingimbi, the music starts about 4. 30 in the morning, gently. ‘The victory belongs to Jesus. The victory belongs to Jesus’; people wake up and line up along the beach, waiting in anticipation, and you can hear murmurs and people talking. The tomb is open and it’s empty and there are cloths lying there. They make a tomb out of a tent, so it’s very culturally appropriate because when people die, when their bodies go back to community, they build shelters and the body sits there in a coffin for a week to two weeks, while ceremonies go on before the bodies go into the ground.

“And so they have this almost like a miniature one of those set up as a tomb and you go there and it’s empty and everyone’s looking around and taking photos and the kids are at the door and looking in. The remarkable thing is that people are not watching a pantomime. They’re not hearing a story or watching a story. They’re in the story, they are part of the story and then they line the beach waiting. And then you see, ‘Is that? What’s that?’ And it’s still dark. And the figure comes walking along the beach in the dark, which takes 15 or 20 minutes to walk along. And then it becomes clear. It’s the risen Jesus, and as he walks up, people are taking photos.

“He stands by the open tomb. He goes into the middle of the worship area where there’s a cross in the ground and stands there. Women come out and kneel and put their hands out. And the whole story is alive. By that time, there are 200 people there and then Jesus wanders off and everyone goes home and it’s six o’clock in the morning.

“And they come back at 10 for communion then go home, then they come back at eight o’clock at night and worship through to midnight or one o’clock.”

The church in this community is led by four couples, five older women and two older men. Over this Easter weekend, all of these leaders were in sync with one another.

“And for me, the great joy was that of those four couples, all of them have been students at Nungalinya and I’ve been their Dean, and of the older women, all of them too, have been students at Nungalinya at some point over the last five years and I’ve been their Dean. One of the old men was a student at Nungalinya when my dad was on the teaching staff at Nungalinya 40-something years ago.

“So we wonder if we’re making a difference. And a lot of the time we take it on faith that we are. But then we get a situation like Easter at Milingimbi or the Gumatj Bible Dedication at Yirrkala the week before, and we know that God is making a difference and that we’ve been invited into this very, very sacred space, this overlap and the overlap of the cultures and that Christ is alive.

“And the Yolŋu, the Aboriginal people, are witnessing to the rest of us in a very powerful way, they’re witnessing to us about the grace of God.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?