Dr Dianne Rayson is one of those people who possess the admirable quality of precise speech. It’s a quality she seems to have developed in different ways and for different reasons.

For example, her study in three distinct but overlapping subject areas – Rayson has earned a Doctorate of Philosophy, along with two Masters degrees in Theology and Public Health – appears to have finely tuned her sensitivity to how words are heard by others.

Bonhoeffer and Gandhi

Bonhoeffer's ‘Religionless Christianity’ and Christian responsibility

She knows how academic philosophy talk sounds to a theologian and vice versa, for example. And she’s fully aware of how both can – and must – apply in the practical realm of the public health sector, in which she has worked in Australia’s Northern Territory and Papua New Guinea. There’s no “academic bubble” talk when you chat with Rayson. Concepts are clear and applied in examples.

Another reason: Rayson is used to working in a contentious space.

Indeed, in describing herself as an “eco-theologian”, she exists in one of those hyphenated areas of study that endures the dubious privilege of being open to critique in both theology or ecology – neither of which tend to fly under the proverbial radar.

Rayson is used to working in a contentious space

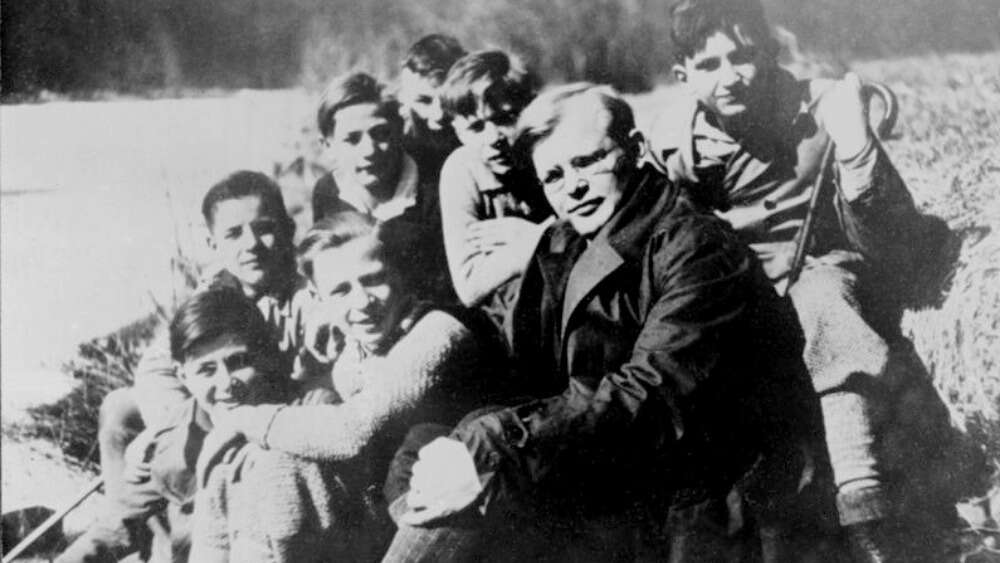

But Rayson’s verbal dexterity has another, even more interesting source: she is a student of one of Christian history’s greats – Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

A German pastor and theologian, Bonhoeffer is best remembered today for his opposition to National Socialism and involvement in a plot to overthrow Nazi leader Adolf Hitler that led to his imprisonment and execution in 1945.

Bonhoeffer’s theological writings are widely regarded as classics throughout the Christian world, but their enduring popularity stems from Bonhoeffer’s equally enduring relevance today.

Questions like: ‘What is a Christian to do when faced with extreme evil being perpetrated by the state?’ and ‘At what point do Christian ethics – the kind that must be fully adhered to in normal times – require different action?’. Or the quintessential question all ethics students have pondered: ‘Is it OK to kill a life in order to save many?’

Rayson is actually one of Australia’s foremost Bonhoeffer scholars. She completed her 2017 Doctorate of Philosophy thesis on the subject of Bonhoeffer’s Theology and Anthropogenic Climate Change: In Search of an Ecoethic. She’s also an elected board member of the International Bonhoeffer Society, Deputy Editor of The Bonhoeffer Legacy: An International Journal and was Convenor of the Australian Bonhoeffer Conference.

Suffice to say that Rayson knows her stuff, the “stuff” she knows is a lot of things, and it is definitely the stuff of Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

And as a result, she has a wealth of insights that could not be more relevant to those who are attempting to live as Christians in 2021.

Learning from Bonhoeffer

During our Zoom interview, I tell Rayson I had originally planned to headline this article “What would Bonhoeffer do about climate change?” Then I read her paper and realised it would not do.

She laughs heartily – she laughs often – and agrees.

“When we talk about a ‘Bonhoefferian’ ethic, we are not talking about the application of principles or a set of rules to overlay onto a particular circumstance,” she says. “Bonhoeffer’s driver is to ask, ‘How do we see Christ working through the moment’ and ‘How do we participate in Christ in this moment?’

“So the correct approach to Bonhoeffer is not asking a WWBD ‘What would Bonhoeffer do?’ type of question, but rather looking at what we learn from Bonhoeffer’s theology and life witnesses that is useful to us to take into our own moment – a moment that is completely different, yet still has a historical context that is continuous from his era to our own.”

When it comes to the crisis of climate change facing humans today, Rayson believes plenty can be learned from Bonhoeffer.

Bonhoeffer, she tells me, was really interested in the relationship between humans and earth. In the 1930s, he wrote an exegesis of Genesis 1-3 entitled ‘Creation and Fall’ during an era when it was quite unusual and unfashionable to even be looking at Old Testament theology.

Bonhoeffer’s theology is centred on relationships – built up from the relationship of Christ in the world and with the world, and extending out from there.

That includes, of course, a network of relationships between humans. Rayson explains that “as we recognise Christ in the world, we see that we are able to be in relationship with earth in the same way that we’re able to be in relationship with each other, because that relationship is mediated by Christ”.

“The whole notion of ecology wasn’t really very popularised yet in the 1930s when Bonhoeffer was writing,” Rayson says. “But I think his theology really pre-empts this notion of a network of relationships and interrelationships and interdependence on each other.”

“And if that’s our starting point, it’s easy then to accommodate what we know scientifically about ecology and about humans not being the overlord of creation. We should see humans as being distinct and having responsibility, but not seeing humans as exceptional in creation. Rather, they are a piece of the whole networked story of creation, and Christ is in and through all of that creation.”

“I think his theology really pre-empts this notion of a network of relationships and interrelationships and interdependence on each other.”

I ask Rayson if this kind of talk is where people start to get worried about pantheism – the doctrine that equates God with the forces and laws of the universe?

She laughs and replies that it is. We both know this is one of the contentious areas for an eco-theologian.

But Rayson confidently says that the apostle Paul didn’t seem to get too hung up about that, and points to one of the oldest hymns we have – the portion of Colossians 1 which talks about Christ being in and through all things and through him, all things holding together.

“So we can’t completely disregard the notion that God is in creation around us and among us. We can’t completely ‘other’ God from our experience of the world around us,” she says.

Plus, Rayson notes, this kind of dualistic thinking – with its emphasis on the division between mind and body – has really become a key influence more recently, since the Enlightenment. And, while there is a distinct dualistic influence even in Paul’s writing, through Stoicism and other Hellenistic philosophies – so it’s there from the start of Christianity in some form – this way of thinking really “came into its own” with the rise of Humanism and the ‘ascent of Man‘ as the ‘superior’ force.

In contrast, she points out, the Christian history of the Desert Fathers and Mothers being in the land was especially grounded – with their hands in the soil. As was our history of Celtic Christianity that saw Christ in the everyday and had prayers for milking the cow and kneading the bread.

“And even before for that, our Hebrew heritage is much more of a really earthy, engaged faith where that dualism doesn’t really exist,” she explains. “This really engaged – ‘Earthly Christianity’, as I call it – is a really distinct part of our history that has really been sort of superseded by Enlightenment thinking and mechanistic understanding of the body.”

But in the light of the 2000-odd years of history before it, “it’s more of an aberration, I think than anything that’s more enduring.”

It’s also not one Bonhoeffer ascribed to, Rayson’s thesis makes clear, drawing on his Creation Story exegesis where he describes Adam being taken from the Earth as humans are taken from our Mother’s womb, rendering human’s bond with Earth essential to our humanity:

“… to Bonhoeffer, even Darwin could not have used stronger language,” Rayson writes. “These earthy bodies are not the shells to simply house our spirits. Bonhoeffer says that the human being is a body, in a move pre-empting embedded cognition. We do not have a body and a soul; rather, we are a body and soul, making our materiality, like Christ’s own materiality, implicit in what it means to be human. Bonhoeffer says ‘we are a piece of Earth called by God to have human existence’ and that ‘what is to be taken seriously about human existence is its bond with mother earth, its being as body’.”

Rayson clarifies that she is not saying we should regard all parts of creation as being the same. But, she says, “Christ’s actions have allowed for reconciliation of the whole of creation”.

“It seems hubris to me to think that Christ’s reconciliation work is only sufficient for one species among the plethora – that doesn’t make sense to me because Christ is in and through all things. So, at some level at least, there must be a work of healing going on through the entire creation.”

This is the first part in Eternity’s interview with Dr Di Rayson. Click here to read Part 2: Bonhoeffer and Gandhi and Part 3: Bonhoeffer’s ‘Religionless Christianity’ and Christian responsibility.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?