In the loft above the old Bible Society offices in Beijing, China, abandoned in 1952, someone had hidden a Bible. When China was later coming out of the cultural revolution, a period when owning a Bible had been forbidden, that hidden Bible was remembered and retrieved. It was photographed and became the camera-ready copy from which millions of Bibles were printed as recently as 1989.

In an amazing turnaround, China has gone from being a place where Bibles had to be hidden, to the place where more Bibles are printed than anywhere else on Earth. There is a good chance any Bible you buy, especially from Bible Society, has been printed in China.

A young Australian, David Thorne, had a key role in this transformation. Thorne had a conviction God would use his print production skills for the kingdom.

“I began my life in newspapers in Melbourne, suburban newspapers at that,” recalls Thorne. “But all through that process I was aware that I really had God’s leading hand on my life.” His hunch came true.

“…Many books were destroyed including, as we found out later, most Bibles that existed in China.” – David Thorne

In 1976, he set out for Asia – India, not China. “I went to India to assist a Christian publisher in the north and I actually built a printing press for them,” he tells Eternity. “It was as an income generator.” He was tapped on the shoulder to help the Indian Bible Society, which had a “dramatic leadership change,” to manage its print production.

By 1982, he was helping the Bible Societies of the Asian region run their printing operations – including Australia. In media, being in the right place at the right time is important, and that is where Thorne found himself.

Based in Hong Kong, in the aftermath of the cultural revolution, Thorne describes how he “became very quickly aware of the impact it had had on not only the church but on all educated people. Both libraries and personal possession of books were frowned upon and many books were destroyed including, as we found out later, most Bibles that existed in China.”

Gough Whitlam and Richard Nixon crossed the ocean to reopen relations with China. It is often said it took an ultra-conservative like then US president Nixon to reopen relations between the US and China. Within Christianity, the Bible Society movement took on the role of breaking down barriers.

Thorne is keen to emphasise that the breakthrough came from within China.

The cultural revolution was the era in China of Bible smuggling, and other innovative ways to get Scriptures in. This culminated in mass distributions of Scripture. Some were by balloons launched from Taiwanese islands to the mainland. At that time, Bible Societies sponsored radio broadcasts of Bible readings.

Thorne is keen to emphasise that the breakthrough came from within China. From 1981, local print runs of Bibles began to be produced in China and a copy was brought back by a Japanese Bible Society delegation. The Bible Society movement, sensing change, decided to drop the radio broadcasts and seek to build relationships with Chinese Christians directly.

Thorne recalls: “One of the decisions that the Global Council [of UBS] made at that time was to cease radio broadcasting in favour of having a localised partnership, which they believed, and we now see, was the best way to go. They believed it would enable us to actually produce and distribute Bibles on the ground, rather than operating from without.”

There was no guarantee it would work and “they received enormous criticism” from other Christian agencies, says Thorne. “Hand in hand with our decision was a China Christian Council invitation to join in (very quietly, of course) the process of producing locally.”

“They were about to place an order for 100,000 Bibles with the People’s Liberation Army press.” – David Thorne

But it was not straightforward: “It was challenging to be able to enter into any financial donation process with the Christian Council … They wanted to preserve the sense of the church in China being local and not influenced by foreign activity. But they were happy to receive a donation in kind.

“They were about to place an order for 100,000 Bibles with the People’s Liberation Army press.

“They said, ‘Well, look, why don’t you supply the paper? We are hoping to start the production in six weeks time.’

“At that time I was ordering paper for various Bible Societies collectively. So I just diverted a shipment of 100 tons to Nanjing. And from within six weeks of receiving the green light they had their paper to get started.”

The paper Thorne organised was critical. “It accelerated the opportunity, because at that point the Christian Council had very little working capital. Basically, it was a huge injection of working capital. They could sell at a subsidised cost because they did not have to pay for paper.” Bible Societies still provide the paper for Bibles in China. These days, it ensures poorer people can afford to get Bibles.

Back in the early ’80s, demand for Bibles was enormous.

The People’s Liberation Army press, Thorne remembers, was one of only three web offset presses in China, the sort needed for that sort of print run. “During the ’70s, I guess they had been sustained by printing the Little Red Book. So they were looking for new work.”

Back in the early ’80s, demand for Bibles was enormous. This led quickly to the idea of setting up a printing plant specialising in printing Bibles. “I developed the original specification for approximately 600,000 to one million Bibles a year. But even the idea of printing 600,000 Bibles a year was untested waters. Because of whether permission would be given; even today, approval for quantities produced each year have to be obtained prior to printing.”

Thorne says he deserves the epithet “oh ye of little faith” because his targets turned out to be too small. Last year, in a newer plant, “output was touching 14 million.”

“All of the machinery configuration was set for – if we pushed 12 or 15 hours a day – a capacity for about one million,” remembers Thorne. “Very quickly, we exceeded that. Within the first year, it was 880,000, then the next year was about 1.4, 1.5 million.”

But there had been a lot of opposition from Christian groups to the idea of a printing plant.

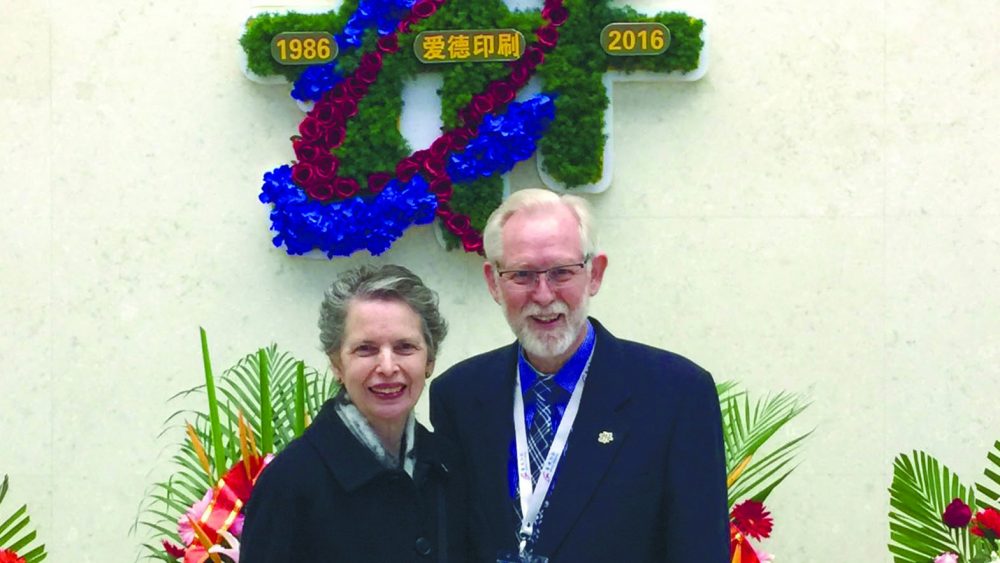

The printing operation Thorne helped set up, Amity Printing Company, turned 30 at the end of last year. It now occupies a modern building the size of several football fields, that opened in 2004. (Amity was forced to relocate from its earlier site and was generously compensated, which meant they built a new plant with capacity to print 20 million Bibles per year.)

But there had been a lot of opposition from Christian groups to the idea of a printing plant. “There was a lot of scepticism and stories floating around that Bibles were just being printed and put into warehouses. They said that the wool was being pulled over our eyes. That continued into the 90s.”

Just after the printing plant was announced, Thorne got a phone call. “I was having a quiet spell after church and the Hong Kong leader [of a mission society] called me and said ‘David, you are deluded, it will come to nothing. The authorities will take advantage of your financial input and not one Bible will get to the public.’”

“Even today, some foreigners and overseas church groups still think China does not allow Bibles…” – David Thorne

The opposition did not go away quickly. “The big pressure from other agencies was ‘Okay, you have got something good going here. But you are … not serving the home churches, therefore there is still an enormous need for additional Scriptures.’ That message still exists to some extent. It is only as testimony from the home churches became clear enough to people elsewhere, where they said, ‘We do not have trouble obtaining Bibles. We might have to go to a registered church to obtain them but we are very happy to do that.’”

“Even today, some foreigners and overseas church groups still think China does not allow Bibles, and some churches in the West still raise funds to smuggle Bibles into the country,” Mr Qiu Zhonghui, Amity’s General Secretary, said in a Financial Times story. “They don’t realise those Bibles are probably made here in our factory in China.”

The printing company is jointly owned by Amity Foundation, a Chinese charity set up by local Christians, and the United Bible Societies. At a 30-year anniversary celebration last year, Elder Fu Xianwei, the head of China’s Three Self Protestant Church, said, “We remember the dream of Bishop Ting and Dr Han Wenzao that every Christian in China would have a Bible of their own. That dream has now been fulfilled and our hearts are full of joy and thankfulness to God.”

Ting and Han were the key players in getting the Amity Foundation off the ground and remain heroes to Thorne. He adds that as the Chinese church grows the demand for Bibles grows still. “New generations need Bibles.” The days of an absolute drought of the word of God in China are over, but millions of Bibles are still needed.